Programmer Whisper

This website records my snippets, patterns, and some practices.

Go Through Swift Result Builders

- 16 Aug 2021

- swift result-builder

What is result builder?

A result builder (a.k.a function builder since swift 5.1 to 5.3) is a type, which can build result value from a set of structured data through a series of processes.

What can result builder do?

According to Swift Programming Language, by implementing a domain-specific language (DSL) with result builders, you can create nested data structures in a natural, declarative way.

In other words, it help you to design a syntax for createing structured data, such as list or tree.

How to use it?

Currently, one of the most famous result builder is the ViewBuilder in SwiftUI. It would be a good entry to know how to use result builders.

Apply result builder on closure as parameter type

func createView<T>(@ViewBuilder _ content: () -> T) -> some View where T: View {

return content()

}

The example above declares the argument content as view builder by annotating @ViewBuilder on it, and invoke content in its body to build and return the result value.

To use createView, it looks like following:

let view = createView {

Text("Title")

Rectangle()

//... more views

}

print("\(view)") //TupleView<(Text, Rectangle, ...)>

The result would be a TupleView wrapping all the views listed in content.

Apply result builder when defining functions and closures

Note that the content is a closure, it means the attribute @ViewBuilder can also apply to functions:

public extension View {

@ViewBuilder

func `if`<Content: View>(_ conditional: Bool, content: (Self)->Content) -> some View {

if(conditional) {

content(self)

} else {

self

}

}

}

myView.if(showBorder) { content in

content.border(Color.red, width: 1)

}

Apply result builder on computed properties

Another way to use @ViewBuilder is applying it on variable, following is how SwiftUI use it on the protocol View:

@available(iOS 13.0, macOS 10.15, tvOS 13.0, watchOS 6.0, *)

public protocol View {

/// The type of view representing the body of this view.

///

/// When you create a custom view, Swift infers this type from your

/// implementation of the required ``View/body-swift.property`` property.

associatedtype Body : View

/// The content and behavior of the view.

///

/// When you implement a custom view, you must implement a computed

/// `body` property to provide the content for your view. Return a view

/// that's composed of primitive views that SwiftUI provides, plus other

/// composite views that you've already defined:

///

/// struct MyView: View {

/// var body: some View {

/// Text("Hello, World!")

/// }

/// }

///

/// For more information about composing views and a view hierarchy,

/// see <doc:Declaring-a-Custom-View>.

@ViewBuilder var body: Self.Body { get }

}

Then, in SwiftUI, you can customize a view as following:

public struct MyView : View {

public var body: some View {

ZStack {

Text("Title")

Rectangle()

}

}

}

Also, you could combine all those usages to create a wrapper view:

struct CustomView<Content: View> : View {

private let content: () -> Content

init(@ViewBuilder content: @escaping () -> Content) {

self.content = content

}

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Title of Custom View")

content()

}

}

}

let customView = CustomView {

Circle()

}

How it works?

Following snippets from SE-0289 shows the basic idea about how a result builder transforms statements into result value:

// Original source code:

@TupleBuilder

func build() -> (Int, Int, Int) {

1

2

3

}

// This code is interpreted exactly as if it were this code:

func build() -> (Int, Int, Int) {

let _a = TupleBuilder.buildExpression(1)

let _b = TupleBuilder.buildExpression(2)

let _c = TupleBuilder.buildExpression(3)

return TupleBuilder.buildBlock(_a, _b, _c)

}

In the the first code block above, it declares the function build() as a result builder named TupleBuilder, and simply put some data into it.

The second block shows how Swift create a series of transformations to process these data.

In this case, the buildExpression transform the input data into the partial result, then the buildBlock collects and put all partial results into a tuple.

Result-building methods

The transformations which called on a result builder type are known as Result-building methods.

Result-building methods are designed as static methods. When you put structured data into a result builder type, the swift compiler using those methods to constrcut the flow to processing those data.

Following are result-building methods:

static func buildBlock(_ components: Component...) -> Component

// Combines an array of partial results into a single partial result.

// A result builder must implement this method.

static func buildOptional(_ component: Component?) -> Component

// Builds a partial result from a partial result that can be nil.

// Implement this method to support if statements that don’t

// include an else clause.

static func buildEither(first: Component) -> Component

// Builds a partial result whose value varies depending on some condition.

// Implement both this method and buildEither(second:) to support

// switch statements and if statements that include an else clause.

static func buildEither(second: Component) -> Component

// Builds a partial result whose value varies depending on some condition.

// Implement both this method and buildEither(first:) to support

// switch statements and if statements that include an else clause.

static func buildArray(_ components: [Component]) -> Component

// Builds a partial result from an array of partial results.

// Implement this method to support for loops.

static func buildExpression(_ expression: Expression) -> Component

// Builds a partial result from an expression.

// You can implement this method to perform preprocessing — for example,

// converting expressions to an internal type — or to provide additional

// information for type inference at use sites.

static func buildFinalResult(_ component: Component) -> FinalResult

// Builds a final result from a partial result.

// You can implement this method as part of a result builder that

// uses a different type for partial and final results, or to perform

// other postprocessing on a result before returning it.

static func buildLimitedAvailability(_ component: Component) -> Component

// Builds a partial result that propagates or erases type information

// outside a compiler-control statement that performs an availability

// check.

// You can use this to erase type information that varies between the

// conditional branches.

For each result builder type, it needs to implement at least one result-building method – buildBlock.

With buildBlock implemented, a result builder type creates the simplest flow to build result value as following:

@resultBuilder

struct CustomBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: String...) -> [String] {

return components

}

}

When apply @CustomBuilder to some closure, Swift will interpret it as following:

@CustomBuilder var custom_builder {

"word"

"list"

}

// The CustomBuilder might be interpreted as following snippet

var custom_builder: ()-> [String] = {

return CustomBuilder.buildBlock("word", "list")

}

Furthermore, if the buildExpression is also implemented:

extension CustomBuilder {

static func buildExpression(_ expression: String) -> String {

return expression

}

}

Then the complier will expand the code as following:

var custom_builder: () -> [String] {

let _a = CustomBuilder.buildExpression("word")

let _b = CustomBuilder.buildExpression("list")

return CustomBuilder.buildBlock(_a, _b)

}

Just like what it does on TupleBuilder.

As more and more result-building methods are implemented, it can support more complex building process – such as if-else, for-loop, or checking availability.

Also, if you are familer with C++ and interesting in how swift implements result builder, you can refer to the source BuilderTransform.cpp to dig more detail.

But for now, let’s focus on how the result builder combines these methods and demystify it in an easier way – log and trace how does it work.

Go through result-building methods by creating custom result builder

In this section, a result builder type called GradientBuilder will be created step by step and shows how result-building methods work. Also, You can get the source of GradientBuilder here.

Let’s think about what features are required for a result builder to generate gradient:

- Developer can put series of colors into it.

- The product should be a gradient object – such as LinearGradient or AngularGradient in SwiftUI.

- buildBlock

To match the basic requirement above, it can simply declare GradientBuilder as following:

@resultBuilder

enum GradientBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Color...) -> LinearGradient {

print("\(#function)")

return LinearGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: components), startPoint: .leading, endPoint: .trailing)

}

}

To show the result of GradientBuilder in Playground, use following code:

struct GradientPreview: View {

var gradient: LinearGradient

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Gradient Preview")

Rectangle().background(gradient).foregroundColor(.clear)

}.padding()

}

init(@GradientBuilder builder: ()->LinearGradient) {

gradient = builder()

}

}

PlaygroundPage.current.setLiveView(GradientPreview {

Color.red

Color.green

Color.blue

}.frame(height:120))

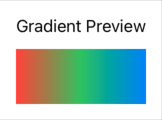

It looks like:

And logs as following:

1 buildBlock(_:)

Furthermore, to make GradientBuilder support more than LinearGradient, you can overload buildBlock:

extension GradientBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Color...) -> AngularGradient {

print("\(#function):angular")

guard !components.isEmpty else {

return AngularGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: []), center: .center)

}

// To make colors continuous between end to start

let colors = components + [components.first!]

return AngularGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: colors), center: .center)

}

}

Then change the type of gradient in GradientPreview:

struct GradientPreview: View {

// var gradient: LinearGradient

var gradient: AngularGradient

//...

// init(@GradientBuilder builder: ()->LinearGradient) {

init(@GradientBuilder builder: ()->AngularGradient) {

gradient = builder()

}

}

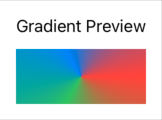

The new result should be:

and it logs:

1 buildBlock(_:):angular

- buildExpression

Sometimes, it prefers to use custom colors rather than built-in colors, and the designer might specify the color by RGBA32 directly – something like (r: 127, g: 56, b: 201, a: 127).

So, it would be good to make GradientBuilder supports both Color class and numeric-represented color.

Also, you can overload buildBlock to support numeric-represented color like below:

typealias RGBA = (red:Int, green:Int, blue:Int, alpha:Int)

extension GradientBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: RGBA...) -> LinearGradient {

let colors = components.map { rgba in

Color(red: Double(rgba.red)/255.0,

green: Double(rgba.green)/255.0,

blue: Double(rgba.blue)/255.0,

opacity: Double(rgba.alpha)/255.0)

}

return LinearGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: colors), startPoint: .leading, endPoint: .trailing)

}

}

But, unfortunately, this approach has some problem in usage, and is difficult to extend.

First, the buildBlock requires all data should be the same type. It means you can not write something like this:

GradientPreview {

Color.red

(127, 181, 200, 127)

Color.blue

}

Secondly, in this case, every time a new input type is added, 2 buildBlocks need to be overloaded for LinearGradient and AngularGradient.

Finally, the color-gradient mapping appears repeatedly in each buildBlock, it’s ugly and hard to maintain.

To solve these problems, buildExpression comes in useful:

typealias RGBA = (red:Int, green:Int, blue:Int, alpha:Int)

extension GradientBuilder {

// Remove overloaded buildBlock

// static func buildBlock(_ components: RGBA...) -> LinearGradient {...}

static func buildExpression(_ color: Color) -> Color {print("\(#function): color")

return color

}

static func buildExpression(_ rgba: RGBA) -> Color {

print("\(#function): rgba")

return Color(red: Double(rgba.red)/255.0,

green: Double(rgba.green)/255.0,

blue: Double(rgba.blue)/255.0,

opacity: Double(rgba.alpha)/255.0)

}

}

With buildExpression implemented and overloaded, GradientBuilder can supports various types of data. To go further, if you want support more types, it just need to implement another buildExpression.

typealias RGBAF = (red:Double, green:Double, blue:Double, alpha:Double)

extension GradientBuilder {

static func buildExpression(_ rgbaf: RGBAF) -> Color {

print("\(#function): rgba float")

return Color(red: rgbaf.red, green: rgbaf.green, blue: rgbaf.blue, opacity: rgbaf.alpha)

}

}

Now, the GradientBuilder can use as below:

GradientPreview {

Color.red

(0, 255, 0, 255)

(0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 1.0)

}

The snippet above shows the same result as previous version, but it will log as following:

buildExpression(_:): color

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:):angular

Just like what we talk about in previous section.

- buildFinalResult

Although GradientBuilder can support different input data type now, is still has similar issue on its output.

To make a custom result builder to support different output easily and extensible, the buildFinalResult method should be implemented.

extension GradientBuilder {

static func buildFinalResult<T>(_ component: T ) -> T {

print("\(#function)")

return component

}

}

The block above shows a generic buildFinalResult which only receive component then return it directly.

This simple method help us observe how buildFinalResult works:

buildExpression(_:): color

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:):angular

buildFinalResult(_:)

Note that the buildFinalResult (if implemented) is always called at the end of the outmost block. It should be the last mile of a result builder.

Back to GradientBuilder, in order to simplify and reduce buildBlcok, it needs to consider what should be kept and what not. Since there are two output types now, it would be better to move all output related code into buildFinalResult:

@resultBuilder

enum GradientBuilder {

//static func buildBlock(_ components: Color...) -> LinearGradient {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Color...) -> [Color] {

print("\(#function)")

// return LinearGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: components), startPoint: .leading, endPoint: .trailing)

return components

}

}

extension GradientBuilder {

// Remove this overloaded function, extract useful part into buildFinalResult

//static func buildBlock(_ components: Color...) -> AngularGradient {

// print("\(#function):angular")

// guard !components.isEmpty else {

// return AngularGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: []), center: .center)

// }

// let colors = components + [components.first!]

// return AngularGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: colors), center: .center)

//}

}

Then, create buildFinalResult to process the new output from buildBlock:

extension GradientBuilder {

// static func buildFinalResult<T>(_ component: T ) -> T {

// print("\(#function)")

// return component

// }

static func buildFinalResult(_ component: [Color]) -> LinearGradient {

print("\(#function):linear")

return LinearGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: component), startPoint: .leading, endPoint: .trailing)

}

static func buildFinalResult(_ component: [Color]) -> AngularGradient {

print("\(#function):angular")

guard !component.isEmpty else {

return AngularGradient(colors: [], center: .center)

}

let colors = component + [component.first!]

return AngularGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: colors), center: .center)

}

}

Now, comparing the logs with our first version:

// without buildFinalResult

// ... buildExpressions

buildBlock(_:):angular

// with buildFinalResult

// ... buildExpressions

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

Again, to add more output type, it only needs to create another buildFinalResult:

extension GradientBuilder {

static func buildFinalResult(_ component: [Color]) -> RadialGradient {

print("\(#function):radial")

return RadialGradient(gradient: Gradient(colors: component), center: .center, startRadius: 0.0, endRadius: 30.0)

}

}

- buildEither(first:), buildEither(second:), and buildOptional(_:)

With buildBlock, buildExpression, and buildFinalResult, result builder can produce complex and flexible result from a data flow. But it can do more.

Actually, it can support flow control on its data flow – just like what @ViewBuilder does:

var body : some View = {

if failed {

Text("Action failed:\(message)")

} else {

Button("Action") {

// do something

}

}

}

Apply the selection statement on GradientBuilder should looks like:

var useRYB: Bool = true

GradientPreview {

(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0)

if useRYB {

Color.yellow

} else {

Color.green

}

(0, 0, 255, 255)

}

To support thoes if-else statement, buildEither(first:) and buildEither(second:) are implemented as following:

static func buildEither(first component: [Color]) -> [Color] {

print("\(#function)")

return component

}

static func buildEither(second component: [Color]) -> [Color] {

print("\(#function)")

return component

}

Note that the type of the arguments first and second are array of Color rather than Color. Because the block in if-else statement might contains multiple data. Also, it outputs multiple data to outer block. And this behaviour affects the implementation of buildBlock

So, it needs update buildBlock, make its input an array of Color array:

@resultBuilder

enum GradientBuilder {

static var test = 0

// static func buildBlock(_ components: Color...) -> [Color] {

static func buildBlock(_ components: [Color]...) -> [Color] {

print("\(#function)")

// return components

return components.flatMap { $0 }

}

}

Then, since the output of buildExpression would be the input of buildBlock, it also need update those methods:

// static func buildExpression(_ color: Color) -> Color {

static func buildExpression(_ color: Color) -> [Color] {

print("\(#function): color")

// return color

return [color]

}

// static func buildExpression(_ rgba: RGBA) -> Color { ... }

static func buildExpression(_ rgba: RGBA) -> [Color] { ... }

// static func buildExpression(_ rgbaf: RGBAF) -> Color { ... }

static func buildExpression(_ rgbaf: RGBAF) -> [Color] { ... }

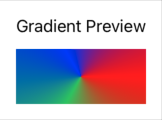

Now, the GradientBuilder works again, and we can see the result of RYB == true should be following:

Also, RYB == false shows:

The called sequence about result-building methods are listed below:

// RYB == true

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildEither(first:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

// RYB == false

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildEither(second:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

The above log has been indented for a clearer structure. In this simple if-else structure, all inner blocks start with buildExpression, following with buildBlock, then invoke build buildEither to summarize the result and output to outer block.

The only difference is buildEither(first:) or buildEither(second:).

Now, let’s dig it deeper, considering following structure:

var useRYB: Bool = true

var useOrange: Bool = true

GradientPreview {

(1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0) // Red

if useRYB {

Color.yellow

} else if useOrange {

Color.orange

} else {

Color.green

}

(0, 0, 255, 255) // Blue

}

What will happen when useRYB is ture? what happen when useRYB is false?

Actually, it will executes as following:

// useRYB == true, useOrange == true | false

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildEither(first:)

buildEither(first:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

// useRYB == false, useOrange == true

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildEither(second:)

buildEither(first:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

// useRYB == false, useOrange == false

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildEither(second:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

Note that when useRYB is true, it invokes buildEither(first:) twice. and when useRYB is false, but useOrange is true, it calls buildEither(second:) first, then buildEither(first:).

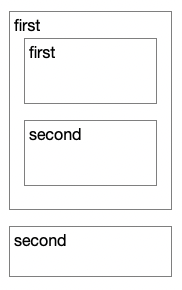

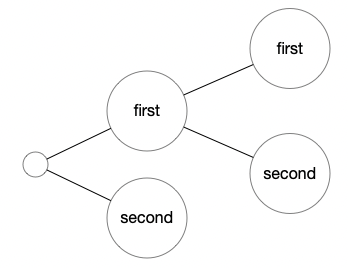

So we can imagine the structure of if-elseif-else as follows:

And if can convert to a binary tree:

And the call sequence is from the leaf to the root.

For more detail, please refer to Result Transformations or Selection Statements.

There is a small piece of selection statement we are not talk about yet, when there is only one block after if:

GradientPreview {

Color.red

if showBlack {

Color.black

}

}

To solve this problem, it implements buildOptional as following:

static func buildOptional(_ component: [Color]?) -> [Color] {

print("\(#function)")

return component ?? []

}

Note that the input of buildOptional might be null, but the output should not be. And If wer execute and log the “if showBlock” statements, it looks like following:

// showBlack false

buildExpression(_:): color

// ----------- no expression and block execute

buildOptional(_:)

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

// showBlack true

buildExpression(_:): color

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildOptional(_:)

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

It can find that the role of buildEither(first:) and buildEither(second:) is repalced by a single buildOptional.

Now, with buildEither(first:), buildEither(second:) and buildOptional(_:), a result builder can support if, if-else, and if-else-if statements. Furthermore, since switch is another form of if-else-if, it also support switch too.

- buildArray

Another important control-flow is loop. To support loop statements, result builder requires developer to implement buildArray:

extension GradientBuilder {

static func buildArray(_ components: [[Color]]) -> [Color] {

return components.flatMap { $0 }

}

}

Note that the input of buildArray is also an array of Color array. Because each iteration should create a block, and buildArray collects and processes those blocks.

The execution sequence of buildArray looks like:

GradientPreview {

for i in 0...5 {

(0.2*Double(i), 0.5, 0.5, 1.0)

}

}

// Logs

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildBlock(_:)

buildArray(_:)

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

- buildLimitedAvailability

Finally, let’s talk about the buildLimitedAvailability. The purpose of this method is shown in its name – to support “if #available” checking.

When the buildLimitedAvailability implemented, developer can checking availablity as following:

GradientPreview {

(1.0, 1.0, 1.0, 1.0)

if #available(iOS 11, *) {

Color.red

} else {

Color.blue

}

(255, 255, 255, 255)

}

And the sequence of execution like:

// For iOS 11 or later version

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

buildLimitedAvailability(_:)

buildEither(first:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):angular

// For other cases

buildExpression(_:): rgba float

buildExpression(_:): color

buildBlock(_:)

// buildLimitedAvailability(_:) is not called

buildEither(second:)

buildExpression(_:): rgba

buildBlock(_:)

buildFinalResult(_:):gradient

The difference between ‘if #available’ and ‘if’ might be confusing. It looks like that the buildLimitedAvailability is not necessary, and can use ‘if’ statement instead of. It’s because for GradientBuilder, there has no availability issues; no matter what type you input – Color or tuples, the only dependence is SwiftUI.

But thinking about other case, for example, ViewBuilder, then buildLimitedAvailability would be needed.

@available(macOS 10.15, iOS 13.0, *)

struct ContentView: View {

var body: some View {

ScrollView {

if #available(macOS 11.0, iOS 14.0, *) {

LazyVStack {

ForEach(1...1000, id: \.self) { value in

Text("Row \(value)")

}

}

} else {

VStack {

ForEach(1...1000, id: \.self) { value in

Text("Row \(value)")

}

}

}

}

}

}

The snippet above is from SE-0289. it shows the example that buildLimitedAvailability is necessary. But why?

The reason is about how ViewBuilder implement its buildEither(first:) and buildEither(second:) :

static func buildEither<TrueContent, FalseContent>(first: TrueContent) -> _ConditionalContent<TrueContent, FalseContent>

static func buildEither<TrueContent, FalseContent>(second: FalseContent) -> _ConditionalContent<TrueContent, FalseContent>

When the function is specialized in above example, it becomes:

static func buildEither(first: LazyVStack) -> _ConditionalContent<LazyVStack, VStack>

static func buildEither(second: VStack) -> _ConditionalContent<LazyVStack, VStack>

It can be noticed the LazyVStack and VStack always appear, regardless of availability. It makes a compilation error.

To solve this issue, ViewBuilder implement buildLimitedAvailability as following to erase type information:

static func buildLimitedAvailability<Content: View>(_ content: Content) -> AnyView { .init(content) }

Now, the buildEither(first:) and buildEither(second:) would be inferred to:

static func buildEither(first: AnyView) -> _ConditionalContent<AnyView, VStack>

static func buildEither(second: VStack) -> _ConditionalContent<AnyView, VStack>

It can be compiled successfully on both macOS 11, iOS 14, and earlier version.

Go back to GradientBuilder, after implementing those building functions, now GradientBuilder have following abilities:

- Developer can put series of colors into it.

- The color can be represented as Color, or tuples named ARGB and ARGBF.

- The product should be a gradient object – includes LinearGradient, AngularGradient, and RadialGradient.

- Developer can use if-else and for-loop to constrict the gradient.

- Also, it support availability checking to seperate gradient from different OS and version.

At this point, GradientBuilder is complete. But there are some details worth discussing.

Other Details

- What type can resultbuilder apply on? What are the differences among those?

You might notice that GradientBuilder is declared as enumeration type, but ViewBuilder is structure type; and Swift says you can apply @resultBuilder to “a class, structure, enumeration to use that type as a result builder”. So, what’s the difference among those?

Actually, if you try following code, it shows the differences:

@resultBuilder

enum EnumBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Int...) -> Int {

components.reduce(0) { $0 + $1 }

}

}

@resultBuilder

struct StructBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Int...) -> Int {

components.reduce(0) { $0 + $1 }

}

}

@resultBuilder

class ClassBuilder {

static func buildBlock(_ components: Int...) -> Int {

components.reduce(0) { $0 + $1 }

}

}

print("\(MemoryLayout<EnumBuilder>.size)") // 0

print("\(MemoryLayout<StructBuilder>.size)") // 0

print("\(MemoryLayout<ClassBuilder>.size)") // 8

let _ = StructBuilder()

let _ = ClassBuilder()

let _ = EnumBuilder() // error: 'EnumBuilder' cannot be constructed because it has no accessible initializers

For the enum and struct, the memory sizes are both 0, but for class, it is 8. It seems due to the difference between Reference Type and Value Type.

In addition, for enum, if and only if the initializer is implemented, otherwise it cannot be constructed.

Also, according to the semantics of result builder, it does not require any variables; in this perspective, enum would be the first choice.

- Oerloading result building methods The GradientBuilder support multiple input and output types by overloading buildExpression and buildFinalResult. But it can do more with overloading.

For example, currently, the gradient built by GradientBuilder is evenly distributed; but sometimes, you might want to specify the color location. To meet this requirement, GradientBuilder should allow Gradient.Stop as input. So, the following overloading functions added:

typealias StopExpression = Gradient.Stop

typealias StopComponent = [StopExpression]]

typealias ColorStop = (color: Color, location: CGFloat)

static func buildExpression(_ stop: StopExpression) -> StopComponent {

return [stop]

}

static func buildExpression(_ stop: STOP) -> StopComponent {

return [Gradient.Stop(color: stop.color, location: stop.location)]

}

Now, GradientBuilder can accept Gradient.Stop and a color-location tuple as input. But it’s not enough, because the buildBlock cannot process array of Gradient.Stop. Let’s add the support for Gradient.Stop:

static func buildBlock(_ components: StopComponent...) -> StopComponent {

return components.flatMap { $0 }

}

Same, it needs overloading buildEither(first:), builderEither(second:), and other result building methods to support Gradient.Stop. In fact, it shows that you can create another path to process the input data by overloading.

This technique is useful for some case, for example, in ViewBuilder and other built-in builder, it’s common to have an buildBlock to process empty statement:

static func buildBlock() -> EmptyView

With this overloaded function, ViewBuilder returns EmptyView directly without invoking unnecessary call stack.

- Generic on Result Builder

Finally, let’s talk about the use of generics on the result builder. Here is SequenceBuilder, a function builder (the predecessor of result builder) implemented using generics. First, it declares several generic buildBlock and buildExpression. Then, it has a generic enum Either which is a variant of the original typelist in Loki(Actually, it’s a combination of typlist and enum with assoicated values, very clever.) With these generic methods and types, SequenceBuilder provides the ability to “build arbitrary heterogenous sequences without loosing information about the underlying types”.

Comparing to the GradientBuilder, which process array of color at run-time, the SequenceBuilder handles series of data at compile-time by generic programming. It creates result builders in a more efficient and flexible way.

At the same time, the generic result builder has its disadvantages:

- It’s hard to understand and expertize generic metaprogramming.

- It’s hard to support variadic input, especially when input types are heterogenous. For example, both the ViewBuilder and SequenceBuilder can support upto 10 views only. If you want more, you need to extend another buildBlock and buileExpression by yourself.

Normally, create a custom result builder does not need use generic, but if the result builder need to process opaque type and protocol, then generic implementation might be a better solution.

Conclusion

Let’s summarize a list of how to customize the resultbuilder:

- Declaring a type with @resultbuilder.

- the type might be Class, Structure, or Enum.

- Create buildBlock(_:)

- the basic form of buildBlock would be buildBlock(_: Component…) -> Component

- It can also be various overloaded functions, such as builcBlock(_:C1) -> C, builcBlock(_:C1, _:C2) -> C, builcBlock(_:C1, _:C2, _:C3) -> C …

- Considering what type of Component should be; normally, it would be better to define Component as Array

where E might be a input type of buildExpression(\_:). - Check if it needs buildBlock for empty statement.

- To support various input types, implement buildExpression(_: Expression) -> Component

- To support different output types, implement buildFinalResult(_: Component) -> FinalResult

- buildExpression -> buildBlock -> buildFinalResult works correctly.

- To support conditional statement, implement buildEither(first:), buildEither(second:) and buildOptional(_:)

- check that buildOptional(_:) deal with null input correctly.

- To support for-loop, implement buildArray(_:)

- To support availablity checking, implement buildLimitedAvailability(_: Component) -> Component

- Check if type should be erased in buildLimitedAvailability. If its need erase the type, the type erasure might be helpful.